In the years that have followed on from Grenfell, a tragic event that still lives on in the memory, a series of changes have been made to fire safety regulations in England and Wales.

Culminating in the Building Safety Act 2022, a landmark piece of legislation heralded by former housing minister Robert Jendrick as “biggest change in building safety for a generation”, the new regulations have sought to rapidly raise standards for building fire safety.

It’s now been some time since the initial changes came into effect, while the Building Safety Act 2022 has recently come into full implementation. So, what impact have the new changes had? And what more needs to be done?

A closer look at the recent changes to fire safety legislation

One of the key pieces of legislation to come out of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry was the banning of the flammable cladding and insulation materials that were deemed responsible for spreading the blaze.

The inquiry concluded that aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding – essentially two thin sheets of aluminium bonded to a polyethylene (PE) core – “acted as a source of fuel”, causing the fire to spread quickly around the building.

The material was soon banned from external wall systems of high-rise buildings over 18m in height. Following another fire stoked by combustible cladding in Bolton, in a building that was only 17.84m tall, the ban was extended to buildings over 11m in 2020.

Further revisions were made in 2022 to bring hotels, hostels and boarding houses within the scope of the ban and to prohibit the use of metal composite materials with a PE core from the external wall systems of all new buildings, regardless of size or use.

Beyond the flashpoint of combustible materials, the Fire Safety Act 2021 and Building Safety Act 2022 have sought to implement more robust processes for evaluating building fire safety, setting new obligations for proprietors and subjecting construction firms to greater regulations.

The changes aim to “go faster and further to promote fire safety” and include lowering the thresholds for mandatory fire sprinkler systems, installing wayfinding signage for fire services and introducing a new Building Safety Regulator with powers to impose harsher penalties for malpractice.

What are the positives of the new fire safety regulations?

The changes to fire safety legislation that have emerged in the wake of Grenfell signal a step in the right direction, with work underway to remove flammable cladding and update fire safety processes in line with the new standards.

Remedial work is underway

One of the Government’s main priorities has been to identify the buildings that share the same flammable ACM cladding that was responsible for spreading the fire at Grenfell. The figures have risen steadily, with the latest data suggesting there are 496 of these buildings in England.

Remedial works have faced lengthy delays, mainly due to disputes between leaseholders and developers over who should be responsible for paying. In the end, the Government has fronted most of the cost, and works are finally taking place.

As of December 2023, 96% of the 496 high-rise buildings with ACM cladding have either started or completed remediation work. However, this data does not account for the buildings over 11m that have recently come into the scope of the ban.

Improved regulatory framework

Recent legislative changes call for a more onerous and proactive approach to fire safety across the design, construction and operational phases of a building, setting out the responsibilities of different parties more clearly and holding those that fail to meet these obligations to account.

The Fire Safety Act 2021, for instance, requires the ‘responsible persons’ of a building – generally the owner or an appointed fire marshal – to update their fire risk assessment to include a review of the building’s structure, external walls and flat entrance doors.

In addition, the new Building Safety Regulator has been granted increased powers to impose unlimited fines and prison terms of up to two years on property owners and developers who fail to comply with the new regulations.

Greater awareness of the dangers of plastics

If anything, the gravity of the Grenfell tragedy and subsequent scrutiny of the UK’s cladding crisis has raised awareness of the dangers of plastics within the built environment, spotlighting an issue that had previously received little attention.

Not only have plastics like PE been shown to pose a major risk to fire safety, but as the case of the Grenfell firefighters diagnosed with terminal cancer shows, they also contain dangerous chemicals that seriously threaten human health.

Flammable cladding is only the tip of the iceberg, with many people only now beginning to question the construction industry’s long-standing reliance on plastics.

Learn more about the fire risks of plastics below.

What are the shortcomings of the new fire safety regulations?

There’s no doubt that the recent changes to fire safety legislation are already having a positive impact, with the removal of dangerous cladding helping to protect thousands of residents. What is concerning, however, is the number of buildings that are still at risk.

Other dangerous materials are still in use

To date, remedial works have been largely confined to buildings with Grenfell-style ACM cladding. Efforts to remove other types of dangerous cladding, such as high-pressure laminate cladding and other plastics like PVC, have made considerably slower progress.

As of December 2023, of the 950 high-rise buildings identified as having dangerous non-ACM cladding, only 24% have completed remediation, leaving 719 buildings susceptible to cladding-related fire risks.

Progress has been even slower on buildings between 11m and 18m, with only 21% of mid-rise buildings with flammable cladding of any kind completing remediation.

Many buildings still aren’t covered by the legislation

Another aspect of the legislation that has raised questions is the type of buildings that the ban on combustible materials applies to.

After initially limiting the ban to high-rise residential buildings, hospitals, care homes and student accommodation, the government extended the scope to include hotels, hostels and boarding houses, while also lowering the height threshold for blocks of flat to 11m.

Combustible materials can still be used, however, in the external walls of other types of buildings, including many public buildings, sports stadiums and low-rise blocks of flats that don’t meet the 11m threshold.

The legislation only applies to external walls

The ban on combustible materials has so far been limited to the external walls of buildings. This is understandable, given that flammable cladding can quickly cause a fire to spread vertically, but it also overshadows the many fire risks that exist in other parts of a building.

Flammable plastic materials like PE, PVC and HDPE are still routinely used in a variety of products, including pipework, window frames, coverings, guttering and roofing, posing serious risks to fire safety.

To truly safeguard the built environment and its inhabitants, a more holistic approach to building design will need to be implemented, with other components coming under the same scrutiny currently being levelled at cladding.

So, what more needs to be done?

In recent years, more evidence has come to light regarding the safety of plastics, laying bare the risks that these materials pose and substantiating the arguments that more extensive bans need to be put in place.

As a material with a naturally low melting point, plastic has no part to play in the fire safety design of buildings and only introduces unnecessary risks. Not only has it been shown to quickly spread fires, but it also releases toxic fumes when exposed to high heat.

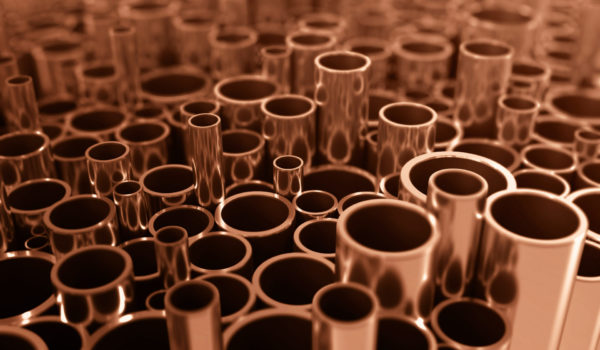

Despite these risks, plastics continue to be specified in construction projects, even when safe and sustainable alternatives are readily available. In plumbing, for example, metals like copper are naturally resistant to fire and also provide the benefit of being infinitely recyclable.

Other solutions exist across the breadth of the built environment, from composite recycled cladding to reclaimed tiles for roofing. But until stronger regulations are put in place, the construction industry’s dependence on plastics will remain largely unchallenged.

Tired of the plastics greenwash? Want to learn more about the sustainable credentials of copper? Subscribe to our newsletter or check out some of our other news items.